Wednesday, January 30, 2019

Critical Bearings: His Dark Materials Illuminated, Edited by Millicent Lenz and Carole Scott

Overview

His Dark Materials Illuminated, edited by Millicent Lenz and Carole Scott (Wayne State UP, 2005), is an intriguing but frustratingly uneven study of Philip Pullman's work. The essay collection carries strong advance praise from several relevant scholars, and it has been favorably reviewed in at least one academic journal, but I found most of the essays to be missed opportunities on the part of their contributors to engage in a serious way with Pullman.

As I am not within the scholarly milieu, not writing specifically for other scholars, nor particularly interested in seeking acceptance for my work within their publications, my opinions may be rather peripheral, and shouldn't carry too much weight. Nevertheless, as I'm reading and thinking carefully about how best to learn from and perhaps to teach His Dark Materials, besides reading Pullman's own comments in essays and interviews and brushing up on some of his most conspicuous sources and literary touchstones, I've also been wading into the existing scholarship, to see if there is anything bright and shiny there worth stealing (with proper attribution, of course) and bringing back to a wider audience. So let's begin with HDM Illuminated. For along with its dross of shortcomings--which may well just be in the eye of this beholder, or endemic to the scholarly-essay-compendium form, or both--there is some gold here.

Following the editor's introduction, "Awakening to the Twenty-first Century: The Evolution of Human Consciousness in Pullman's His Dark Materials," which sounds promising, but proves a little breathless and new-agey, the collection is organized into three sections:

- Reading Fantasy, Figuring Human Nature

- Intertextuality and Revamping Traditions

- Pullman and Theology, Pullman and Science Fiction

Which, unfortunately, are about as faddish and baggy as they sound. There follow biographical and bibliographical notes. Each section is prefaced with an overview; individual essays do not have abstracts, and most carry only a few works cited and endnotes. Still these tangential remarks, citations (especially from interviews and speeches of Pullman's I wasn't previously aware of), and bibliographical signposts proved to be some of the most interesting material in the book.

Frankly, I don't feel like I actually learned very much about Pullman's story, themes, or characters--the things I care most about--nor about the process of his own reading, writing, and revision--the things I wanted to know more about. Most of the authors in the collection seem to treat Pullman's story as simply an experimental case study for whatever theoretical perspective or research topic they are concerned with: ideology, reader-response, various takes on theology, etc. Some of this, again, is built into such a collection and into the broader academic discourse, with its publishing imperative; some of this looseness, with most essays talking past one another from their rather arbitrary arrangement among the three sections, could also be the effect of the editors' choices. I'd be interested to see the original call for papers; I'm in contact with and hope to talk to at least one or two of the authors, though sadly before the book saw publication, Millicent Lenz, the editor, passed away.

Thoughts on the essays

Awakening to the Twenty-first Century: The Evolution of Human Consciousness in Pullman's His Dark Materials, by Millicent Lenz

I have my critiques of this piece, as of the collection as a whole, but I am appreciative of the work Lenz does here to establish Pullman as a subject for serious study. Perhaps it would be too pejorative, then, to note that she undercuts that seriousness by taking a quote from "New Dimensions Radio" for her epigraph, alongside a passage from The Amber Spyglass. The latter, as she hasten to point out, is the winner of the prestigious Whitbread Prize; the former, a self-help website's glib quote of the day. After all, my own project is engaged with just such bridge-building between scholarship and popular culture; perhaps we just don't have the same taste in listening. Lenz's dedication to the project of Pullman scholarship is evidenced by her having previously published an essay on Pullman in Alternative Worlds of Fantasy Fiction, co-edited with Peter Hunt, and here she continues to build on the idea of a creative evolution of consciousness, albeit without grounding that endeavor in neuroscience or even psychology, nor explaining why she does not do so. Besides citing Pullman's Arbuthnot lecture (which I haven't been able to track down), among other statements by the author from across his series as well as outside of it, Lenz draws on studies of Wagner and PB Shelley, as well as stray quotes from Thoreau and Beowulf, to make her case for Pullman's mythic storytelling as a representation of and blueprint for enlightenment, in the intellectual as well as the spiritual sense. It's a convincing enough argument, though I'm already partial to the thesis and thus would have liked to see less enthusiastic skipping around and more sustained analysis of the actual consequences of such a mode of consciousness. I think Lenz glosses over the inherent contradictions, or at any rate the paradox, of her faith in all of us undertaking our own process of mythopoesis, not only cheering on Lyra and Pullman in theirs. Instead of squarely addressing the requirement for Will and Lyra to return each to their real world, or to tell true stories in the world of the dead, or to account for less persuaded readers' claims that God is still a vital part of their lives--and not only the "Echoes in the space where God has been," in Pullman's provocative phrase, which she seems to believe is now normative or at least desirable--Lenz's essay concludes by opening the floor to the other authors. Her admirable invocation to "enrich the quotient of Dust in our literary universe" (13) would land with more force if Lenz had, if only in a footnote, wrestled a little more with what that multifaceted mote of a word might mean.

Reading Dark Materials, by Lauren Shohet

Eschewing a flashy two-part title--the only piece in the collection which dispenses with this badge of the contemporary academic essay--and mercifully lacking any overt theoretical framework, Shohet's "Reading" is also one of the strongest in the book. From an opening densely packed with well-chosen quotes from HDM, Shohet puts her finger on the implications of innocence and experience "in the modes of reading...and the stakes of good reading for the trilogy's interrelated models of art, identity, and ethics" (23). In this essay, she does what I am trying to do: not to impose a reading on Pullman, but to understand the reading which his story, by its story, content, form, and presuppositions, is teaching. To do so, I agree with Shohet that we need to build upon some of those implicit presuppositions: "Like Renaissance allegory, HDM creates a legible world that demands adequate reading for more than cognitive reasons...symbolic (exploring Lyra and Will's relationship as the relations between art/storytelling ['the Lyric'] and desire/action ['Will']); moral (plumbing the nature of persons and communities in the different worlds the novels depict); and 'anagogical' or apocalyptic (the battle between opposing supernatural forces that includes resolving the problem of death)." She points us to Hamilton's work on Spenser if we want to know more about allegory, but immediately dives back into the story, picking up on Dr Lanselius' hint of a Renaissance background for the alethiometer. Giving continual points of reference in Milton, Shohet elegantly negotiates the crucial problems of death, erotic love, and metaphysical vitalism in Pullman, before closing with a humbler and yet more effective appeal to hear "The Republic of Heaven" in the bells that close the story.

Second Nature: Daemons and Ideology in The Golden Compass, by Maude Hines

Drawing on Louis Althusser, Michel Pecheux, and Pierre Bourdieu, the essay applies the claim "it is impossible to get outside of ideology" to Pullman's work (37). While it may be compelling sociology, it doesn't have much to teach us about the story, which actually seems concerned with something like human nature--deeply connected to the material world--capable of transcending ideology, or at any rate constructing a novel, continually renovating ideology resting upon the possibility of measuring the truth and telling true stories. In particular, Hines explores the way in which Lyra's world treats daemons as normative, while to us they are fantastic. She makes some uncomfortable parallels, such as between the racist pseudosciences of phrenology and physiognomy and Lyra's ability to read peoples' emotions and social status through their daemons, or between her near brush with intercision and gang rape or castration, which are implicit in the text, but do not add up to significantly aid our understanding of what these things, shocking in themselves, are doing within the story. To me, they are plainly metaphors evoking human nature and evil, respectively, both of which seemed ruled out by Hines' ideological presuppositions. What I take to be Hines' central claim, when she is speaking of the witches' view of Lyra's destiny: "Destiny works like ideology here; nature, like free will," actually seems interesting, but it is confused and not developed by making references to "familiar fairy-tale narrative" and "Freudian family romance," rather than looking closely at what Lyra understands of her destiny, and what role her daemon plays in it (40).. In short, what actually happens in the story is much more interesting.

Dyads or Triads? His Dark Materials and the Structure of the Human, by Lisa Hopkins

Another intriguing title, and as I read over the examples of twos and threes, of which a few are pretty interesting--the conflict between Will and the man he kills because "neither of them saw the cat" (though you might say that neither of them saw their daemons, either), or the claim that "there are in fact three events that could be interpreted as constituting this betrayal" (52, though I disagree with the three she suggests being the only candidates)--I was mostly looking for Hopkins to discuss the key passages where Lyra and Will intuit that, besides their physical bodies and their daemons, "'there must be another part, to do the thinking!'" and where, when they ask her about it towards the end of the book, Mary Malone tells them, '''St Paul talks about spirit and soul and body.'" She winds up, "'So the idea of three parts in human nature isn't so strange.'" I felt the same could be said for this essay: So what? Hopkins ends right where the real work would begin, with questioning and unpacking these claims about the "triune nature of the human" (55). How, since it is an idea in Augustine (and in Plato and Aristotle, for that matter, while the children's initial insight sounds almost Cartesian) how is it that this "fundamentally cuts against" the complex doctrine of the Trinity, which Augustine, following his read of Paul, was influential in developing? Even without firsthand knowledge of the philosophers and theologians, a quick search would have pointed Hopkins to the relevant Bible verses, so that we could at least begin to think about the theology embedded in Pullman's story, as Mary plainly invites us to do. And then to top it off, the "Alethiometer" feature on the Random House website, cited in the notes, seems to be defunct. But I can't blame that on Hopkins.

Northern Lights and Northern Readers: Background Knowledge, Affect Linking, and Literary Understanding, by Margaret Mackey

I was excited about this one, again, because of what I was hoping and expecting to find in it. Lenz, in her intro, notes "Margaret Mackey's 'Playing in the Phase Space'[...] comments on Pullman's use of the concept and explores the textual 'play' that crosses media boundaries" (14). I wanted to hear more about play in Pullman's work, the ludic, if you like, as it relates to reading Pullman, but instead got a playful essay with practically nothing to say about Pullman's story. Instead, Mackey describes driving past hay trucks in winter, connects this to Dust and the North, says a little about the presuppositions and background knowledge readers bring to texts and a little about studies to that effect, hers and Gelertner's, and their relation to the classic reader-response literature. It would be a useful essay for someone writing a paper in an education class, I imagine, but it doesn't yield any new insights into Pullman. Alas, I can't even find a copy of her other essay anywhere.

Pullman's HDM, a Challenge to the Fantasies of JRR Tolkien and CS Lewis, with an Epilogue on Pullman's Neo-Romantic Reading of Paradise Lost, by Burton Hatlen

Pullman's Enigmatic Ontology: Revamping Old Traditions in HDM, by Carole Scott

"Without Lyra we would understand neither the New nor the Old Testament": Exegesis, Allegory, and Reading The Golden Compass, by Shelley King

Rouzing the Faculties to Act: Pullman's Blake for Children, by Susan Matthews

Tradition, Transformation, and the Bold Emergence: Fantastic Legacy and Pullman's HDM, by Karen Patricia Smith

In line with the approach traced by Shohet, though not quite with her insight into Pullman's work, the five essays in the middle section of the book address themselves to the task of elucidating Pullman's use of canonical literary sources. I consider them together here for the simple reason that though each treats a different source or cluster of sources, the upshot of each of these essays is pretty much the same: readers with a serious interest in Pullman, who are fired by his imagination and want to understand his work as fully as possible, and thus to see some of what inspired him, in turn, would do best to read those major sources for themselves. The essays are fine as secondary texts attesting to and gathering evidence of influences Pullman himself has repeatedly avowed his indebtedness to, but they do little to synthesize the effects of these influences taken together, which would help bring out and begin accounting for the complex tensions at work between them in his work as a whole. For an admirable work of that kind, I recommend Laurie Frost's encyclopedic The Elements of His Dark Materials, which carries a laudatory foreword by Pullman himself. (There are no doubt other dissertations and monographs out there by this time--I've seen references to a work by Gray which looks fascinating, but I have yet to read it.)

At around twenty pages each, Hatlen's and King's entries are the most substantial in terms of length in the entire collection. Lacking sufficient focus, though, they read like the outlines of book-length studies, ranging over interesting material and raising intriguing connections without contributing anything substantially new about the significance of Pullman's use of his sources. Hatlen makes the claim, echoed by many Lewis scholars, such as Dickieson and Ward, that Pullman's avowed distaste for the Narnia books does not prevent him from producing "a kind of inverted homage to his predecessor." Fair enough, and a topic well worth treating further, but Hatlen's essay instead tries to rope in Tolkien and Milton as well. Unfortunately, Hatlen discredits himself as a reader of Tolkien at the outset, with the dismissive, "Tolkien's achievements as a literary scholar were relatively modest" (76). Relative, perhaps, only to his impact as a novelist, but even that is by no means obvious, given the importance of his two great essays, "Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics," and "On Fairy-Stories." The discussion of Milton may be valuable as a summary of the main currents of formidable scholarship by Fish, aligned with Lewis' orthodox read of Paradise Lost, and Empson, aligned with Pullman's Blakean conception, but it does little to illuminate Pullman's story.

King's essay revolves around a conceit much less commonly remarked upon than Hatlen's, connecting a "theological scholar-exegete," Nicholas of Lyra, with our main character, as well as noting her surname's reference to Dante (112). Though acknowledging that the connection between the names may be spurious, or, as she puts it, "merely serendipitous," King spins out an expanded version of Shohet's insight about layers of meaning with respect to medieval exegesis. She references the alethiometer and other characters' names in a somewhat scattered way, but also makes important connections to the Christian fantasist in whose shadow the Inklings themselves once stood, George MacDonald, and to an instance of dust imagery in Bunyan's epochal Pilgrim's Progress. One more cogent argument concerns the minor prophetic undertone's of Will's father's mantle, and his understanding of his mother's use of that phrase. Despite its somewhat playful indulgence of breadth at the expense of depth (one I can relate to), King's piece proves to be one of the richest and liveliest in the collection. Not least, because it winds up with commentary from Pullman on one of the least known of his key sources, Kleist's "On the Marionette Theatre," from an interview the full transcript of which is evidently no longer available.

Placed between the two longer essays, Scott's suffers from being too short. She takes on too much for ten pages: "This essay will explore how Pullman has used his three major literary sources--Milton, Blake, and the Bible--to reinterpret the ontology of humankind's moral and ethical universe, and to redefine humankind's quest for a meaningful purpose in life and the individual's responsibility in defining good and evil" (95). Again, Shohet tackles similar themes, but through the lens of imagery of reading does a much better job limiting her essay to a manageable scope. Inevitably, without a similarly focused image or question, Scott can do little more than present broad the broad strokes of what would make an interesting book in its own right (one someone may well have written by now). Though citing a number of relevant passages from Pullman as well as those three sources, countless others are left out. For one crucial example, perhaps because it is discussed, albeit briefly, by King, Asriel's discussion of Genesis does not figure in Scott's essay. Fresh fields of study, such as the witches' beliefs about Yambe-Akka, or shamanism, are referenced only glancingly, but would have represented a much better use of Scott's evident acumen. Tasked with completing the work of editing the collection after Lenz' passing, though, she no doubt had many other pressing concerns.

Matthews brilliantly concentrates her essay on Pullman's debt to just one author, William Blake. (Though in noting the strangeness of the mulefa, she can't pass up references to Gulliver's Travels and The Lord of the Flies.) Besides analyzing passages of various poems from across Blake's cosmos, providing a jumping-off point for further reading, Matthews ties the verbal and thematic echoes she discovers there in Blake back to equally well-chosen moments in Pullman. Thus, beyond the familiar sweeping statements about innocence and experience, we get some new insights into the importance of the body and sexuality, into daemonic separation and settling, and into how these relate to the narrative voice in the novel. That storytelling voice is perhaps Pullman's least appreciated master-stroke, one he muses on in his essays frequently, and Matthews begins to show a way to investigating it further, noting its indebtedness to poetry through allusions and epigraphs as well as celebrating its prose: "drawing in its imaginative energy on the soaring movement of comic heroes in its battles and journeys, but also, like Blake's writing, demanding access to the key myths of its culture" (133). Her closing critique of HDM's "linear reading...that loses some of the dialectical power of opposition and contraries," is well taken, hinting at the tension between Pullman's statements about the freedom of the reader and the evident didactic turns his story seems to take. However, I would want to dig deeper into the way in which Pullman illustrates a world saved by innocence as well as experience before buying into Matthews' argument fully. My only other quibble is that the essay would also have benefited from at least acknowledging the important role of Blake's illustrations, since Pullman's delight in, and dabbling in, visual art is well known.

Smith takes the opposite tack, cobbling together an agglomeration of references to recent generations of YA fantasy authors whose work Pullman has most likely never read. She imparts a measure of structure to this attempt to map a genre he disavows onto Pullman through a framework of "Five Key High Fantasy Conventions," more or less boiling down the Campbell mono-myth to a still more manageable (and distorting and reductive) handful of tropes (136). Like Hatlen's proposal about his debt to Lewis, Smith's rubric of "Troubled Young People with an Important Life Mission," "Excursions into Invented Worlds," and the rest is certainly there in Pullman's story, whether he likes to talk about it or not. But this is neither all that controversial nor particularly interesting. Pullman understandably (and correctly, I think) stresses what makes his work different, and while telling passages to that effect come out in Smith's essay, such as the valedictory renaming of the harpy Gracious Wings by Lyra, contra Tolkien, or Will and Lyra's return to their own worlds, contra Lewis, there is practically no attempt at analysis. The failure to engage with Pullman, then, is not total; however, the absence of any more substantive point of reference for what fantasy is or why it matters in the first place, such as Tolkien's "On Fairy-Stories," or of a more sustained comparison of Pullman over against just one representative work of substance, such as Cooper's The Dark is Rising, makes the essay little more than a vague, misguided survey.

"And He's A-Going to Destroy Him": Religious Subversion in Pullman's HDM, by Bernard Schweizer

Rediscovering Faith through Science Fiction: Pullman's HDM, by Andrew Leet

Taken together, despite or perhaps due to their contradictory theses, these essays provide a helpful point of departure for discussions of religion in the books. And ultimately that's all these essays can ever be: points of departure, from which we would do well to depart, without being drawn into an interminable wrangle about which nothing can be proved either way. Without retreading too much of the ground covered by others who focus on Pullman's appropriations of Milton, et al., Leet and Schweizer do a fair job of compiling essays, reviews, and interviews where Pullman's beliefs and their representations in the story are at issue. Plainly, based on all that has been said--by Pullman, by his narrator, by his readers--totally opposite and equally coherent conclusions can be drawn. Secondary sources from further afield, ranging from Flannery O'Connor to Pope John XXIII, from Kierkegaard to Camus, can be mustered along either side of the debate; or rather, Pullman can be pulled in to support any number of lofty arguments on religion and faith which such authors might speak to, or to provide endlessly fresh material for one's own understanding of theology, whatever that might be.

Circumventing the Grand Narrative: Dust as an Alternative Theological Vision in Pullman's HDM, by Anne-Marie Bird

An instructive case-study in the delights of postmodern theory: we are masterfully extricated from academic cul-de-sacs generated by the theory itself. Besides weaving together statements from Marx, Freud, Nietzsche, Heidegger, Derrida (across four different books!), and their interpreters, Bird even manages to engage with Pullman now and then. Before proceeding to circumvent it, the essay admirably sets out to tackle Dust, which certainly deserves careful attention, given that at least one of its meanings is precisely such conscious attention. It is ironic, then, that by bringing out its complexity--"Dust is transformed from a conventional metaphor for human physicality/mortality into an ambiguous, almost mystical presence in which everything coexists"--Bird veers immediately into posing the false dichotomy between that "conventional metaphor" and "a means of fusing together and thus equalizing everything" (190). Conveniently, she thus dodges away from the actual development of the idea through the story, the various and changing perspectives on Dust which indeed drive the story, making Dust a highly unconventional metaphor, and the story nothing less than a grand narrative, with all its wealth of meanings. Instead, this liberated, free-floating Dust, this principle of "intrinsic amorphousness," is very agreeable to the postmodernist program of irreproachable ambiguity, what Bird takes to be Derrida's "free play" (196). Thus, she simply substitutes one conventional metaphor for another more to her liking.

Unexpected Allies? Pullman and the Feminist Theologians, by Pat Pinsent

"Eve, Again! Mother Eve!" Pullman's Eve Variations, by Mary Harris Russell

Two stronger essays close out the collection. Contra Bird, Pinsent demonstrates the perennial viability of careful scholarship, thoroughly supporting the claim which is well summed-up in her introduction: "when people think deeply about traditional religious ideas and are prepared to reassess and reinterpret the Bible and tradition without taking as axiomatic the meanings usually read into them, there may be a surprising degree of kinship between their conclusions" (200). She convincingly traces Pullman's affinities with feminist critiques within the church across a range of topics, concluding with Lyra's "growth into her role as the new Eve" (208). This is where Russell picks up the thread, forcibly restating Pinsent's argument in Pullman's own terms: "When the new Eve is ready for the new creation, built on truth, the old Authority, built on a lie, must vanish" (212). As Pinsent notes about that image of the new Eve, these lines of Russell's could apply to the Virgin Mary just as well. Discussions of Mrs Coulter and Mary Malone, as well as of Christian myth, provide context for Lyra's approximations to this truth. At last Russell juxtaposes the series of climactic moments around which Pullman's entire tale converges: the love between Will and Lyra and the salvation of Dust; their daemons' settling and their returning to their separate worlds; the end of the Authority, "'a mystery dissolving in mystery'" (220). To me the only connections still missing here are between this final release and that of the dead from their underworld, on the one hand, and the demise of Lyra's parents in their fall with the terrible Regent, on the other. These are further corollaries of that combination of knowledge-seeking and love which is the truth of Lyra's story, and which the story so powerfully encourages us to make our own.

To that end, I'm continuing to read Pullman, his commentators, and the rich tradition of which we are all a part and to which we all contribute. More bibliographies and reviews to follow.

Thursday, January 24, 2019

Publications and Fandoms: Philip Pullman Bibliography

Since last night, when I aired some less-than-charitable thoughts about His Dark Materials Illuminated at the end of another day-late Gamecool episode, I've been feeling some remorse. On the one hand, I meant what I said: the texts in that volume are not terribly satisfying as critical essays; on the other hand, they're still interesting enough. I don't know if I could do any better.

And anyhow, I cordially dislike most critical essay-writing of this type. I'm no academic, so whatever I have to say is bound to be marked by that. But I love to be proved wrong: works like Shippey's Author of the Century, Flieger's Splintered Light, Olsen's Exploring The Hobbit, Anderson's Annotated Hobbit, and Tolkien's own critical tours de force, The Monsters and the Critics and On Fairy-stories, have all been truly illuminating. In trying to broaden my knowledge and sharpen my critical acumen, I've begun reading some of the Barfield which Flieger recommends and draws upon for her argument, as well as giants in the field of criticism, such as Morrison's Playing in the Dark, Auerbach's Mimesis, and Frye's Anatomy.

At any rate, I still mean to write out a more coherent and thorough review of the Lenz/Scott book. So that's what I'll do over the next few posts!

As I continue to read through more scholarly/academic and other fannish/mercenary secondary literature that's out there about Pullman, I also stand by my call for help. If you've read any of it and have some thoughts, let me know. If you have, it's probably because you've cited it in a paper, so send that to me, too, while you're at it. There could be a scholarship in it for you!

Mercifully, there are several existing bibliographies of Philip Pullman:

There's the one in the back of Laurie Frost's The Elements of His Dark Materials (and the author's preferred 2006 edition, The Definitive Guide)

And at the end of HDM Illuminated, edited by Millicent Lenz and Carole Scott

Online at isfdb, orderofbooks, and LibraryThing (helpfully pointing to many of his introductions, afterwords, etc.)

And at BridgeToTheStars.net

Douglas Anderson's Wormwoodiana (just one entry when I checked, but still impressive)

So that's a start. As for the Lyra stories' internal chronology...whew. Still working that out! Meanwhile, I'll also keep advocating what I see as the more important task, the labor of love: close reading of his work, and of relevant primary sources. For that list, see the course page.

And anyhow, I cordially dislike most critical essay-writing of this type. I'm no academic, so whatever I have to say is bound to be marked by that. But I love to be proved wrong: works like Shippey's Author of the Century, Flieger's Splintered Light, Olsen's Exploring The Hobbit, Anderson's Annotated Hobbit, and Tolkien's own critical tours de force, The Monsters and the Critics and On Fairy-stories, have all been truly illuminating. In trying to broaden my knowledge and sharpen my critical acumen, I've begun reading some of the Barfield which Flieger recommends and draws upon for her argument, as well as giants in the field of criticism, such as Morrison's Playing in the Dark, Auerbach's Mimesis, and Frye's Anatomy.

At any rate, I still mean to write out a more coherent and thorough review of the Lenz/Scott book. So that's what I'll do over the next few posts!

As I continue to read through more scholarly/academic and other fannish/mercenary secondary literature that's out there about Pullman, I also stand by my call for help. If you've read any of it and have some thoughts, let me know. If you have, it's probably because you've cited it in a paper, so send that to me, too, while you're at it. There could be a scholarship in it for you!

Mercifully, there are several existing bibliographies of Philip Pullman:

There's the one in the back of Laurie Frost's The Elements of His Dark Materials (and the author's preferred 2006 edition, The Definitive Guide)

And at the end of HDM Illuminated, edited by Millicent Lenz and Carole Scott

Online at isfdb, orderofbooks, and LibraryThing (helpfully pointing to many of his introductions, afterwords, etc.)

And at BridgeToTheStars.net

Douglas Anderson's Wormwoodiana (just one entry when I checked, but still impressive)

To sum up, the publication order for first editions of Pullman's works seems to run as follows, with selected adaptations, duplications, etc. briefly noted:

Early Novels (1970's)

Having completed his studies, married (1970) and started a family, Pullman begins his publishing career with a pair of hard-to-find, at times hard-to-read literary novels.

1972 - The Haunted Storm

1978 - Galatea

Writing and Teaching (1978-1995)

According to Cengage Encyclopedia, Pullman teaches at the middle school (1970-86) and university level (1986-95). Featuring the not-to-be-overlooked Sally Lockhart books and valuable autobiographical sketch "I have a feeling this all belongs to me," by the tail end of these years Pullman is wrapping up his teaching career and turning his full attention towards an ambitious story inspired by Paradise Lost.

1978 - Using the Oxford Junior Dictionary

1979 - Ancient Civilizations

1982 - Count Karlstein, or the Ride of the Demon Huntsman (rewritten from earlier school play script)

1985 - The Three Musketeers (unpublished play performed at Polka Children's Theatre)

1985 - The Ruby in the Smoke (TV adaptation feat. Billie Piper and Matt Smith! '06 )

1986 - The Shadow in the Plate (...North US '88)

1987 - How to Be Cool (TV adaptation in '88; here's ep 3)

1989 - Spring-Heeled Jack

1990 - The Broken Bridge

1990 - Frankenstein (from a play at Polka Children's Theatre)

1990 - The Tiger in the Well

1992 - The White Mercedes (reprinted as The Butterfly Tattoo in '98)

1993 - Sherlock Holmes and the Adventure of the Limehouse Horror (from a play at Polka Children's Theatre)

1993 - Aladdin

April 1993 - "I have a feeling this all belongs to me" (autobiographical sketch for Something About the Author, vol. 65)

1994 - The Tin Princess

1994 - Thunderbolt's Waxwork

1995 - The Gas Fitters' Bal1 (reprinted in The Adventures of the New Cut Gang '11 and together with its predecessor in Two Crafty Criminals! '12)

Master Storyteller (1995-2025), comprising the period between His Dark Materials and The Book of Dust. Pullman achieves notoriety, accolades, and scholarly notice; but note too just how much else he's published over these years, from Clockwork, his "most perfectly constructed story," and companion stories about Lyra's world, to his fairy tales and collected nonfiction--a remarkable, diverse, and as yet little studied body of work.

7/9/95 - Northern Lights (UK)

9/2/95 - The Firework-Maker's Daughter (rewritten from earlier school play script)

4/16/96 - The Golden Compass (US; film adaptation 2007; HBO/BBC series 2019 incorporating material from companion books and LBS; audiobooks narrated by Pullman and full cast '03 and by Ruth Wilson '24; various stage and radio plays including at the Royal National Theatre '03-'05 and BBC 4 '03; the video game released '07 on various platforms contains footage subsequently cut from the film)

11/15/96 - Clockwork, or All Wound Up

7/22/97 - The Subtle Knife (HBO/BBC series 2020)

1998 - Mossycoat (included in Magic Beans: A Handful of Fairytales from the Storybag '11)

1998 - Detective Stories (anthology with preface and introductions; reprinted as Whodunit? '07)

4/1/99 - I Was a Rat! or The Scarlet Slippers

10/10/00 - The Amber Spyglass (HBO/BBC series 2022)

2000 - Puss in Boots (from a play)

10/28/03 - Lyra's Oxford

9/4/04 - The Scarecrow and His Servant

2005 - Lantern Slides (included in HDM 10th Anniversary ed.)

4/3/08 - Once Upon a Time in the North

12/4/09 - The Good Man Jesus and the Scoundrel Christ

8/9/12 - Fairy Tales from the Brothers Grimm: A New English Version

2014 - The Golden Compass Graphic Novel (Fr.; En. trans. Annie Eaton 2015)

12/10/14 - The Collectors (audio only; print 2022)

5/30/17 - The Adventures of John Blake: Mystery of the Ghost Ship

10/19/17 - La Belle Sauvage

2017-18 - Daemon Voices (ed. Simon Mason, anthologizing pieces written at various times)

10/3/19 - The Secret Commonwealth

10/15/20 - Serpentine (written c. '04 to be sold at auction fundraiser)

2/22/22 - The Subtle Knife Graphic Novel

4/28/22 - The Imagination Chamber (standalone reprint of Lantern Slides)

10/23/25 - The Rose Field

2025-? What else? Presumably more graphic novels. Perhaps the promised "little green book" about Will? More memoirs? Time will tell. I'm hoping for collections of letters, tweets, and interviews, and the discovery of unpublished notes and drafts...

So that's a start. As for the Lyra stories' internal chronology...whew. Still working that out! Meanwhile, I'll also keep advocating what I see as the more important task, the labor of love: close reading of his work, and of relevant primary sources. For that list, see the course page.

In the spirit of completionism, here are editions of books with prefaces, introductions, and so on contributed by Pullman. Many are collected in Daemon Voices.

2004 NYRB: Lindsay, The Magic Pudding

2005 Folio Society: Burton, Anatomy of Melancholy

2008 OUP: Milton, Paradise Lost

For interviews and writing about Pullman, from the scholarly to the hack, see the continued bibliographies here.

Please help me out and point out any errors or omissions.

Monday, January 21, 2019

Creative Tension: Mujica, King, and Caliphate

For this MLK day, a time of strikes and marches, and hopefully a time for tension and perspective alike, here's a suggested film, text, and podcast.

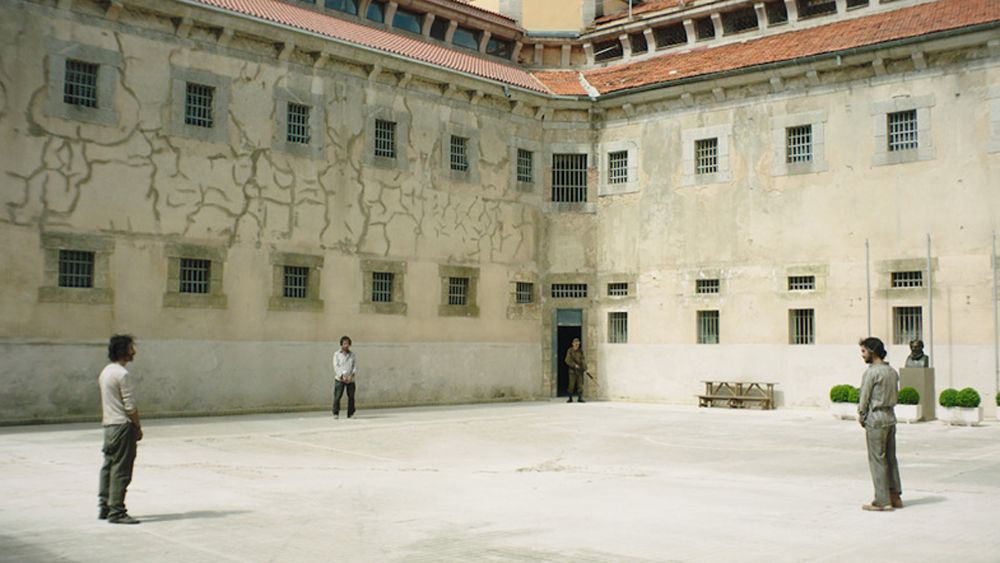

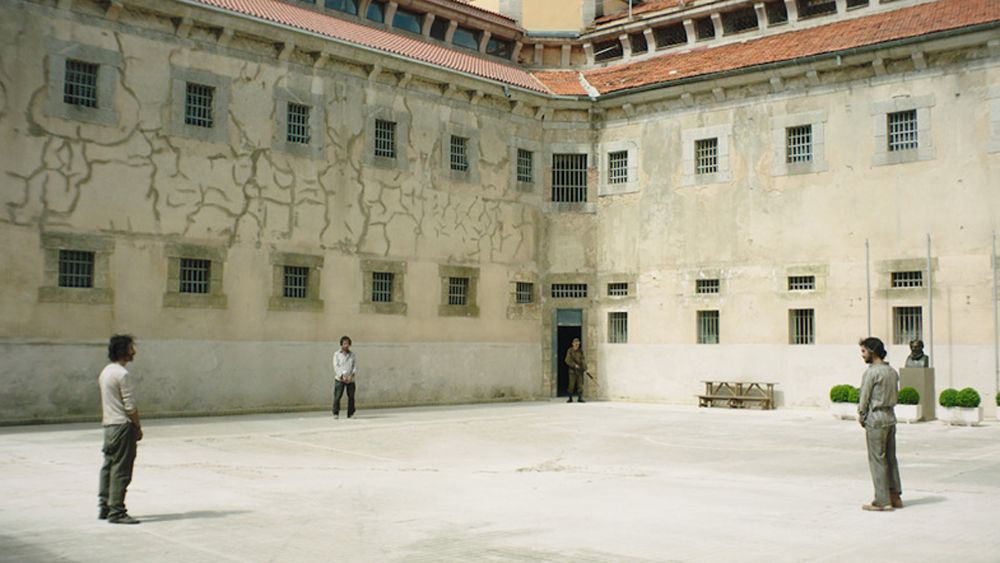

A Twelve Year Night, directed by Alvaro Brechner. The little-known history of Uruguay, a country I love, comes to light as presented through the experience of three political prisoners under the Cold War-era military dictatorship. Unlike so many others, these three survive; indeed, one of them, Jose 'Pepe' Mujica, eventually becomes President.

Letter from a Birmingham Jail, by Martin Luther King, Jr. Among our country's essential readings, it echoes Thoreau's Civil Disobedience, as well as Socrates in the Apology:

A Twelve Year Night, directed by Alvaro Brechner. The little-known history of Uruguay, a country I love, comes to light as presented through the experience of three political prisoners under the Cold War-era military dictatorship. Unlike so many others, these three survive; indeed, one of them, Jose 'Pepe' Mujica, eventually becomes President.

Letter from a Birmingham Jail, by Martin Luther King, Jr. Among our country's essential readings, it echoes Thoreau's Civil Disobedience, as well as Socrates in the Apology:

You may well ask: "Why direct action? Why sit ins, marches and so forth? Isn't negotiation a better path?" You are quite right in calling for negotiation. Indeed, this is the very purpose of direct action. Nonviolent direct action seeks to create such a crisis and foster such a tension that a community which has constantly refused to negotiate is forced to confront the issue. It seeks so to dramatize the issue that it can no longer be ignored. My citing the creation of tension as part of the work of the nonviolent resister may sound rather shocking. But I must confess that I am not afraid of the word "tension." I have earnestly opposed violent tension, but there is a type of constructive, nonviolent tension which is necessary for growth. Just as Socrates felt that it was necessary to create a tension in the mind so that individuals could rise from the bondage of myths and half truths to the unfettered realm of creative analysis and objective appraisal, so must we see the need for nonviolent gadflies to create the kind of tension in society that will help men rise from the dark depths of prejudice and racism to the majestic heights of understanding and brotherhood. The purpose of our direct action program is to create a situation so crisis packed that it will inevitably open the door to negotiation. I therefore concur with you in your call for negotiation. Too long has our beloved Southland been bogged down in a tragic effort to live in monologue rather than dialogue.Caliphate, by Rukmini Callimachi and Andy Mills. A podcast, so it can go with you anywhere, and so it does, or did for me: rough as it was, I couldn't stop listening. In telling the story of ISIS members and going into their territory and into their motivations, the appeal of the call to adventure is turned around, revealed as a force for terrible nihilism in the service of an ideology promising unsullied truth. Difficult as it is to hear, it reminds us of other places too long bogged down in their own tragic monologues, that in this case, we perhaps don't even know the language yet which would permit us to begin a dialogue.

Wednesday, January 9, 2019

Kierkegaard's Works of Love, Sickness Unto Death, and Practice in Christianity

I'm finally running out of Kierkegaard to read, coming to the end of my stack of scholarly paperbacks purchased at a bulk discount from a San Diego bookstore five or so years ago. They're all in good shape except for a few places where the plastic coating the covers is peeling up, and the pages are clean aside from a handful in each book, distributed more or less randomly as far as I can tell, where a previous owner meticulously highlighted and underlined (in some cases multiple times in different colors of pen) a few sentences from among the thousands of pages of pseudonymous authorship. In the margins, this discerning reader abbreviated other titles to confer, and in some of the indices even added page numbers or entries that the editors missed including. I guess anyone who buys and tries to read this much Kierkegaard is bound to be a little weird.

As I've gotten a little behind on my posts, I thought I'd try to bring together some reflections on all three books I've read since last checking in here: Works of Love, The Sickness Unto Death, and Practice in Christianity. This lapse of time, though, means that I remember even less than usual what it was I supposedly read. For one small example, I spent about an hour the other week trying to find a passage about the way Christianity pins something to the end of something else, which Farder Coram's description of the spy-fly in ch 9 of The Golden Compass reminded me of, but I couldn't even figure out which book it came from. Maybe some astute listener will be able to find it someday. I don't like to mark up my books, but I'd make an exception for tracking that passage down at last.

A friend suggested that I make a podcast about Kierkegaard, the way I'm doing with EarthBound, Pullman, and so on, but I can only do so much at once, so it will have to wait for another time. He was writing a rock opera about him, and that seems like a good way to go--a kind of radio drama, with musical interludes, mixing biographical and philosophical aspects of the author's life and his work. But it wouldn't hurt to give everything at least a first read before undertaking something like that, fun as it sounds.

Maybe I'm biased after sinking so many hours into reading this stuff, but it really seems to me that a project like that, bringing more readers to Kierkegaard, more listeners to his ideas, could serve an important role in the society he didn't live to see, but so eerily anatomizes in his writing.

Here's a passage the mysterious previous owner had underlined in yellow, which I also thought was pretty good:

As I've gotten a little behind on my posts, I thought I'd try to bring together some reflections on all three books I've read since last checking in here: Works of Love, The Sickness Unto Death, and Practice in Christianity. This lapse of time, though, means that I remember even less than usual what it was I supposedly read. For one small example, I spent about an hour the other week trying to find a passage about the way Christianity pins something to the end of something else, which Farder Coram's description of the spy-fly in ch 9 of The Golden Compass reminded me of, but I couldn't even figure out which book it came from. Maybe some astute listener will be able to find it someday. I don't like to mark up my books, but I'd make an exception for tracking that passage down at last.

A friend suggested that I make a podcast about Kierkegaard, the way I'm doing with EarthBound, Pullman, and so on, but I can only do so much at once, so it will have to wait for another time. He was writing a rock opera about him, and that seems like a good way to go--a kind of radio drama, with musical interludes, mixing biographical and philosophical aspects of the author's life and his work. But it wouldn't hurt to give everything at least a first read before undertaking something like that, fun as it sounds.

Maybe I'm biased after sinking so many hours into reading this stuff, but it really seems to me that a project like that, bringing more readers to Kierkegaard, more listeners to his ideas, could serve an important role in the society he didn't live to see, but so eerily anatomizes in his writing.

Here's a passage the mysterious previous owner had underlined in yellow, which I also thought was pretty good:

Christ was the fulfilling of the Law. How this thought is to be understood we are to learn from him, because he was the explanation, and only when the explanation is what it explains, when the explainer is what is explained, when the explanation [Forklaring] is the transfiguration [Forklarelse], only then is the relation the right one. Alas, we are unable to explain in this way. If we can do nothing else, we can learn humility from this in relation to God. Our earthly life, which is frail and infirm, must separate explaining and being, and this weakness of ours is an essential expression of how we relate to God...And now since people are so eager to be something, it is no wonder that however much they talk about God's love they are reluctant to become really involved with him, because his requirement and his criterion reduce them to nothing. (WL 101; by this, the page 110 is indicated, and below, my esteemed precursor has written metanoia. On 110, by the line "This is the way Christianity came into the world; with Christianity came the divine explanation of what love is" is written the number 101, closing the infinite loop, turning and turning.)Later, a passage the author emphasizes with italics, I thought was staggering, though there's no additional markings around it, nor for many pages in either direction:

The one who loves presupposes that love is in the other person's heart and by this very presupposition builds up love in him--from the ground up, provided, of course, that in love he presupposes its presence in the ground. (216)Like the Upbuilding Discourses, Works of Love is one of the few books Kierkegaard released under his own name as author, and one of the few overtly confessing Christianity. The degree to which his life is subsumed in his writing, his love for people in his love for God, comes through as much in these earnest deliberations, which ostensibly reflect his real beliefs, as in his poetic creations of pseudonyms, which vary and play with the same themes from a multiplicity of perspectives. He earlier put his Philosophical Fragments and Concluding Unscientific Postscript under the pen-name Johannes Climacus; the next two books after Works of Love both carry the name Anti-Climacus. Where JC is preternaturally honest and abides in doubt, AC is authoritative, demanding, a quixotic knight of faith.

The Socratic definition works out in the following way. When someone does not do what is right, then neither has he understood what is right...But wherein is this definition defective?...it lacks a dialectical determinant appropriate to the transition from having understood something to doing it. In this transition Christianity begins; by taking this path, it shows that sin is rooted in willing and arrives at the concept of defiance, and then, to fasten the end very firmly, it adds the doctrine of hereditary sin... (SUD 92)To fasten the end...well I'll be. Anyhow, time to wrap this up.

That to deny direct communication is to require faith can be simply pointed out in purely human situations if it is kept in mind that faith in its most eminent sense is related to the God-man. Let us examine this and to that end take the relationship between two lovers..."Do you believe that I love you?".... (PC 141)The relentless call to see the difficulty of belief, on the one hand, and the pervasiveness of our dependence upon it, make Kierkegaard's writing essential; the tidbits of his life story that come through make him fascinating and exasperating. When I come to the end of the last few books on my shelf, I'll pick right back up with Either/Or, track down a copy of his student thesis on irony, and get going on the teach-yourself-Danish book I found at the library book sale only a year ago, maybe. Love believes all things.

Tuesday, January 8, 2019

Vox populi

January is a good month for thinking about Greek and Latin roots--hence, for realizing how little you do know, nice as it is to know that little bit. For January comes from Janus, the god of doorways, who with two faces looks forward and back. And more than that, I can't really say. Why should there be such a god? Why should his name still adorn our calendar? I only know that janitor comes from the same door-root. And it's a good time for tidying up, too.

Just a sliver of electronic tidying here, to mention a couple of new projects, or new foci anyhow. Now I'm officially tasked with leading the Signum Academy, I'll be reaching out to people for ideas and suggestions on a number of fronts, but especially for advice about publicity and funding, as those aspects of the endeavor are to me the most mysterious. I suspect a great deal of luck is involved, and having awesome content and teachers, which we do, will help us to seize the opportunity when it comes. But hints about how to prepare in the meantime are appreciated.

The other area of focus is with interview guests for our Night School programming. Alex and I are looking for more people to talk to, so if you know someone who'd like to discuss American poetry, recurrent events, video games, neuroscience, or education, let us know! We're always shooting for the moon, too, with contacts found at the heights of their profession via academia or google searches who turn out to be willing to talk. A number of anime and gaming scholars and luminaries will hopefully be recording with us shortly. With that said, we still haven't been able to get a reply from anyone at MIT's Media Lab or Vox media, but we'll keep trying, honing our craft in the meantime.

A fun game to play, when listening to interviews by the pros, is to try to think what you would ask next in the interview, or to try to guess what they're likely to say next, and see how those things compare. It's a little like how Ben Franklin describes learning to write, in his autobiography:

Text and image copied from that den of aspiring auto-didacts, Project Gutenberg.

Just a sliver of electronic tidying here, to mention a couple of new projects, or new foci anyhow. Now I'm officially tasked with leading the Signum Academy, I'll be reaching out to people for ideas and suggestions on a number of fronts, but especially for advice about publicity and funding, as those aspects of the endeavor are to me the most mysterious. I suspect a great deal of luck is involved, and having awesome content and teachers, which we do, will help us to seize the opportunity when it comes. But hints about how to prepare in the meantime are appreciated.

The other area of focus is with interview guests for our Night School programming. Alex and I are looking for more people to talk to, so if you know someone who'd like to discuss American poetry, recurrent events, video games, neuroscience, or education, let us know! We're always shooting for the moon, too, with contacts found at the heights of their profession via academia or google searches who turn out to be willing to talk. A number of anime and gaming scholars and luminaries will hopefully be recording with us shortly. With that said, we still haven't been able to get a reply from anyone at MIT's Media Lab or Vox media, but we'll keep trying, honing our craft in the meantime.

A fun game to play, when listening to interviews by the pros, is to try to think what you would ask next in the interview, or to try to guess what they're likely to say next, and see how those things compare. It's a little like how Ben Franklin describes learning to write, in his autobiography:

About this time I met with an odd volume of the Spectator. It was the third. I had never before seen any of them. I bought it, read it over and over, and was much delighted with it. I thought the writing excellent, and wished, if possible, to imitate it. With this view I took some of the papers, and, making short hints of the sentiment in each sentence, laid them by a few days, and then, without looking at the book, try'd to compleat the papers again, by expressing each hinted sentiment at length, and as fully as it had been expressed before, in any suitable words that should come to hand. Then I compared my Spectator with the original, discovered some of my faults, and corrected them. But I found I wanted a stock of words, or a readiness in recollecting and using them, which I thought I should have acquired before that time if I had gone on making verses; since the continual occasion for words of the same import, but of different length, to suit the measure, or of different sound for the rhyme, would have laid me under a constant necessity of searching for variety, and also have tended to fix that variety in my mind, and make me master of it. Therefore I took some of the tales and turned them into verse; and, after a time, when I had pretty well forgotten the prose, turned them back again. I also sometimes jumbled my collections of hints into confusion, and after some weeks endeavored to reduce them into the best order, before I began to form the full sentences and compleat the paper. This was to teach me method in the arrangement of thoughts. By comparing my work afterwards with the original, I discovered many faults and amended them; but I sometimes had the pleasure of fancying that, in certain particulars of small import, I had been lucky enough to improve the method of the language, and this encouraged me to think I might possibly in time come to be a tolerable English writer, of which I was extremely ambitious. My time for these exercises and for reading was at night, after work or before it began in the morning, or on Sundays, when I contrived to be in the printing-house alone, evading as much as I could the common attendance on public worship which my father used to exact of me when I was under his care, and which indeed I still thought a duty, thought I could not, as it seemed to me, afford time to practise it.

|

| Birthplace of Franklin. Milk Street, Boston. |

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)